Israel’s Camp in the Wilderness

By Mark Morgan | Exodus

When Israel left Egypt, everything about their day-to-day life changed.

No more would their daily work be ordered by slave drivers. No more would they live in houses or grow their own food in a vegetable patch. Instead, they would have no fixed place of abode and no clear itinerary, having to deal with uncertainty and learn many new ideas as they travelled.

God had promised to guide them to Canaan: a good, broad land;[1] a land flowing with milk and honey.[2]

Yet, from the beginning, God did not lead them around the coast into Canaan, although that would have been the shortest and quickest route. Instead, he led them into the wilderness and across the Red Sea, explaining that if they went the short route and met war immediately, they would seek the security of what they knew, even it it meant returning to Egypt as slaves.[3]

In the wilderness, God provided them with water and food as he led them to Mount Sinai[4] where he proposed a covenant where he would be their God – as he had been the God of their fathers – and would give them laws to keep as a nation. All the people agreed[5] and the covenant was duly made.[6]

A nomadic life travelling through wilderness and desert was very different from the life they were used to, and travelling in such large numbers would make the practical things of life very difficult: food collection, water distribution, cleanliness, childbirth, old age and so on.

Many of the laws God gave them were to maintain social order, some to facilitate their travels and some for when they arrived in the Promised Land. Arranging the camp during their travels would have been very important but difficult.

We don’t know exactly how many Israelites left Egypt, but we know that one year later, the number of able-bodied men ready for war who were 20 years of age or older was 603,550. Allowing for the extra males under twenty and those who were not able-bodied, the number of males would have been about 1.2 to 2 million. If the number of females was similar, the total number of people in the congregation would be 2.4 to 4 million, or possibly even more. These numbers did not include the foreigners who escaped with the Israelites, or the tribe of Levi, which was counted separately using different criteria.

Overall, in Israel’s camp in the wilderness, the layout would need to accommodate roughly 3-4 million people, which would be a logistics nightmare.

Moving millions of people from one place to another takes significant time, and a day is not very long if people need to pack up their tents in the morning, march to another place and then set up their tents in time to sleep that night – possibly having to be ready to move on again the next day.

To make this process easier and quicker, God specified the marching order of the tribes and the camp layout. Just imagine trying to choose a site and set up about 600,000 tents if everyone had to choose their own camp site from a large area with no guidelines, no marked sites, no known orientation or specified neighbours. I’m very confident that it would take more than a day to organise!

God’s camp layout took away some of the uncertainty and inconvenience, so let’s look at what God specified.

Israel was made up of twelve or thirteen tribes, depending on how you counted them. Jacob had twelve sons, but he had also claimed Joseph’s two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim, as his.[7] That made thirteen tribes, except that in the wilderness, God claimed the tribe of Levi as his, so that they were not counted with the rest of the tribes. This choice is highlighted by the layout of the camp, where the Levites were clustered close around the tabernacle.

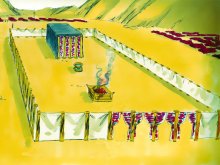

In their camp, the rest of the nation surrounded the Levites, separated into 12 tribes: three on the east, three on the south, three on the west and three on the north, as shown in the diagram below.

The diagram above is schematic rather than being proportionally exact. The size of each tribe’s camp (and even the small family groupings of the Levites) would be much larger than the size of the tabernacle courtyard, so if this was a properly scaled map, the tabernacle would be too small to see.

A second census was taken near the end of their time in the wilderness and the total number of men 20 years of age and over was almost identical (601,730), even though all of the men counted in the first census had died, except for Joshua and Caleb, the only two of the twelve spies who had believed God’s promise that Israel could defeat the nations in Canaan. As a result, they would have been older than any of the other men counted in the second census. The numbers in each tribe varied quite a lot between the two censuses. If the change in number of men over 20 for a tribe is greater than 10%, the box includes an arrow pointing up if the population grew and down if the population reduced. The length of each arrow is proportional to the size of the change.

When God told the nation to move from one camping place to the next, they were to march in an order God specified. The diagram shows the order for each group as a number with a leading ‘#’.

Each group of three tribes had a tribe specified as the leader, and the names of these leading tribes are shown in bold in the diagram above. The diagram assumes that the tribes will surround the tabernacle in the listed order in a clockwise direction, although this is not the only reasonable option.

We are told that Judah was to lead his set of three tribes that camped to the east of the tabernacle (Judah, Issachar and Zebulun) as the nation’s vanguard.

The Levites then took away the pieces of the tabernacle on carts, ready to set them up again on arrival at their destination. Thus, the tabernacle was ready for the furniture when the priests arrived with it.

The second group of three tribes (Reuben, Simeon and Gad) camped to the south of the tabernacle and was led by the tribe of Reuben.

Once Reuben’s tribes had left the campsite, the priests followed, carrying the tabernacle furniture on their shoulders.

Ephraim led the third group of three tribes (Ephraim, Manasseh and Benjamin) that camped at the west of the tabernacle and followed the Levites as they marched.

The last group of three tribes (Dan, Asher and Naphtali) camped to the north of the tabernacle and joined the march last, being led by the tribe of Dan.

Exodus 26:1-37; 36:8-38; 40:2-5; 17-25 tabernacle

Exodus 27:1-19; 38:1-7; 39:39; 40:6; 29 bronze altar

Exodus 27:9-19; 38:9-20; 40:8; 33 tabernacle courtyard

Exodus 30:17-21; 38:8; 40:7; 30-31 bronze basin (no dimensions)

Exodus 40 setting up the complete tabernacle

Numbers 1:1-46 first census (Numbers 2:32, total 603,550)

Numbers 1:27; 49; 50; 53; 2:33 Levites not included in census and their camp was to encircle the tabernacle

Numbers 2:1-31, 34; 10 camping arrangements, marching order

Numbers 3:21-39 census of Levites

Numbers 26:1-51 second census (Numbers 26:51, total 601,730))

During Israel’s 40 years in the wilderness, the overall population of the nation remained almost unchanged. Some tribes, however, grew larger while others shrank. The most extreme example is the tribe of Simeon, whose number of able-bodied men reduced from 59,300 (the third biggest tribe) to become the smallest tribe with only 22,200 about 38 years later. Naturally, we ask, Why? We’re not told directly, but a few details suggest possible reasons. Shortly before the nation entered the land of Canaan and just before the second census, many Midianite women seduced Israelite men into Baal worship and associated sexual immorality. God sent a plague to punish this double unfaithfulness, killing 24,000 Israelites in the process, probably all men. During a gathering of national repentance, a brazenly unrepentant leader brought a Midianite woman into his tent in full view of the nation. He was executed by Phinehas the priest along with his lover, and God praised Phinehas for his action. The record notes that Zimri, the executed leader, was from the tribe of Simeon.

No connection is made in the text, but leaders normally reflect the people they lead. We don’t know what proportion of the 24,000 dead came from the tribe of Simeon, but it may have been a majority. After all, other leaders had already responded by identifying the ringleaders in their tribe and executing them, but the leadership of Simeon was modelling the very behaviour God condemned.

Overall, Simeon’s numbers reduced by 37,100 over 38 years, and this single event, so close to the end of their travels, may have been the greatest contributor to that decline.

As shown in the earlier diagram, some other tribes (Manasseh, Benjamin, Asher and Issachar) grew significantly, but no one event causes a significant increase – the growth of families takes years.

For most people living in a tribal area in the wilderness, all their neighbours would have been from their own tribe. However, at the edges of tribal areas, they may have lived quite close to members of other tribes.

One demonstration of this is found in the rebellion against Moses and Aaron reported in Numbers 16. The leaders of the rebellion are listed as Korah, a Levite from the family of the Kohathites, along with Dathan, Abiram and On from the tribe of Reuben. Is it just a coincidence that the Kohathites camped to the south of the tabernacle between the tabernacle and the camp of Reuben? I doubt it.

Korah probably met and befriended some leaders of the tribe of Reuben because he camped near them. Not considering their existing positions of leadership important enough, they formed a conspiracy with 250 other dissatisfied leaders from other tribes. Moses and Aaron were the target of their discontent, the ones they blamed for withholding the positions of importance they deserved.

Now Moses was a humble man who led the nation by following God’s instructions. Yet these men believed Moses was promoting himself and his family, making up all of the communication with God and the commands he had received. In short, they used their own frame of reference to judge him, assuming that he had the same self-centred motivations as they. Sadly, people with a chip on their shoulder have a habit of locating others with the same problem – birds of a feather flock together.

These men confronted Moses with their censure and self-promotion, demanding the right to take on the duties of God’s chosen priests. Moses knew that their pretensions would be fatal and did his best to dissuade them. When they refused to listen, he set up a “competition” where Korah and his followers would approach God the next morning in their own way with their own incense, while Aaron obeyed God’s commands. God would show who he had chosen.

He did. The earth opened up and swallowed Korah, Dathan and Abiram with their tents and families,[8] while the other 250 leaders were consumed by fire that came out from God. The rebels died, but Aaron the obedient priest survived. Not only so, but if Moses and Aaron had not interceded with God, many more would have died.

Be careful how you choose your friends!

A well organised and closely-packed camp surrounding the tabernacle provided comfort and security for Israel, but it also created two contrasting positions: inside the camp and outside the camp.

Inside the camp, God’s laws kept the nation holy. Most of the nation was to be safe inside the camp.

However, God also gave instructions to exclude some things and people from the camp of Israel. The reason? Cleanliness and holiness.

People with “leprosy”[9] were considered unclean and could not enter the camp. It appears that the disease or diseases described as “leprosy” were highly infectious at certain stages, and at these times people with “leprosy” had to live outside the camp.

Toileting also had to be done outside the camp,[10] and God finishes his instructions with an explanation:

“Because the Lord your God walks in the midst of your camp, to deliver you and to give up your enemies before you, therefore your camp must be holy, so that he may not see anything indecent among you and turn away from you.”

Several other reasons are given for the exclusion of people or things from the camp on a temporary or permanent basis.[11]

The concept of being outside the camp is used in the letter to the Hebrews where we are reminded that, just as some sacrifices were burned outside the camp, so Jesus died for us outside the camp – outside Jerusalem. The writer encourages us to take up our cross and follow him, choosing to suffer the reproach he suffered, seeking the city that is to come.[12]

We’re not told the physical dimensions of the camp, and if you aren’t interested in numbers and estimates, you might as well stop reading this section now! If you are, read on and see what you think.

Earlier, we estimated there were about 600,000 tents in the camp. If each tent was about 10m2 (110 ft2) and we allow a similar area for spacing between tents and providing some paths, that would require 12 km2 (4.6 sq. mi.). A circular camp of that area would be 2.6km (1.6 mi.) in radius.

Note that this gives a population density of almost 300,000 people per square kilometre (780,000 per sq. mi.) which is similar to that of the Ravensbrück concentration camp, about three quarters of the population density of the most crowded slums in the world today and much, much higher (about 40 times higher) than the Gaza strip!

Is there any element of life which allows us to assess whether this camp size would make life difficult or impossible?

There is one aspect of life where God’s laws would make daily life very difficult in a large circular camp: toileting, specifically defecation.

God commanded:

“You shall have a place outside the camp, and you shall go out to it. And you shall have a trowel with your tools, and when you sit down outside, you shall dig a hole with it and turn back and cover up your excrement.”

Now if going “outside the camp” meant travelling to the outside of a circular camp, even with the densely packed camp described above, half of the population would have to walk more than 1.4km (1,500 yards) to go to the toilet and retrace their steps to their tent. No doubt this would help to keep the nation fit, but it would be difficult to maintain.

Imagine, however, if each tribe was separate from the others, like separated slices of a cake as shown in the diagram above. In this case, “outside the camp” could include the spokes of open space that separated the tribes and led in towards the centre of the camp. In such a camp configuration the average distance for toileting would be about 400 metres (440 yards), with a maximum of about 700 metres (770 yards) – still substantial, but much more manageable.

I’m sure the arrangement and shape of the camp would have been adjusted in various ways to make this particular restriction – with its resulting health benefits – workable.

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive the diagrams as well!

If you'd like PowerPoint slides of the diagrams in this post sent free to your inbox, why not sign up for our newsletter here and receive the file as well?

(You can cancel your subscription at any time.)

Notes

| ↑1 | Exodus 3:8 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Exodus 3:17; 13:5 |

| ↑3 | Exodus 13:17-18 |

| ↑4 | Also called Mount Horeb (compare Exodus 31:18–32:19 and Deuteronomy 9:8-17) |

| ↑5 | Exodus 19:8; 24:3, 7 |

| ↑6 | Exodus 24:8 |

| ↑7 | Genesis 48:5 |

| ↑8 | Not all of Korah’s family supported him. Some separated themselves from him and survived (Numbers 26:10-11). Eleven Psalms are declared to be written by the sons of Korah (Psalms 42, 44-49, 84, 85, 87 and 88). |

| ↑9 | The leprosy described in the Bible causes different symptoms and is thus a different disease or collection of diseases from Hansen’s disease, which we call leprosy. Hansen’s disease is not very infectious – most people exposed to it will not catch the disease. |

| ↑10 | Deuteronomy 23:12-14 |

| ↑11 | Soldiers who had killed anyone or touched a dead body (Numbers 31:19-24); any man made unclean by a nocturnal emission (Deuteronomy 23:10-11); law-breakers being executed (Leviticus 10:1-5; Numbers 15:32-36); and possibly some foreigners (see Joshua 6:23). Also, some offerings were to be made outside the camp or some parts disposed of outside the camp (Exodus 29:14; Leviticus 8:17, 9:11; Leviticus 4:11-12; Leviticus 4:21; Leviticus 6:11; Leviticus 16:26-28; Numbers 19:2-10; Hebrews 13:11). |

| ↑12 | Hebrews 13:11-14 |