Kings in the time of Daniel

By Mark Morgan | Daniel

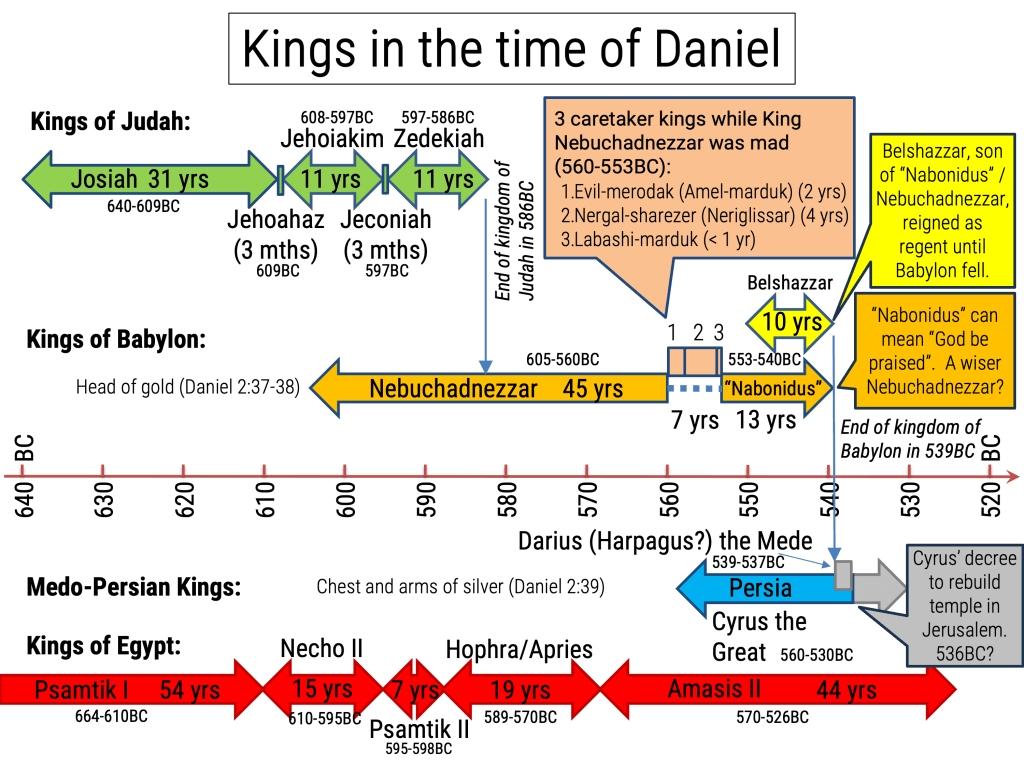

While writing a story about Daniel over the last five years, I knew that I would finally get to the stage where I needed to make decisions about the later kings of Babylon in the time of Daniel. The history in the early parts of Daniel’s life is fairly much agreed upon and fits well with the Bible. However, the agreement fades away as we consider the following fifty years of history. After a lot of study of the Bible’s records – which I consider to be the inspired word of God – I cannot embrace the generally-accepted lists of kings of Babylon, Media and Persia during the sixth century BC (eg. List of Kings of Babylon (Wikipedia) or List of Kings of Babylon (Jatland).

The Bible’s framework for the kings of Babylon, Media and Persia is as follows:

The Bible is not a history book. Rather, it is “profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction and for training in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16). At its core, the Bible is designed to lead people to God, and the history included in its pages simply provides context. I believe that all of the Bible’s historical detail is correct, and vast numbers of archaeological discoveries bear this out. However, since reporting history is not the main aim, the history it includes will never be “complete”. For example, although we are told how Jonah warned the people of Nineveh and inspired the king of Nineveh to repent, we are not even told the king’s name. The Bible is full of such “holes” in historical detail, and the absence of information in it should never be used by believers to argue against other historical or archaeological evidence. That is just as bad a mistake as when historians or archaeologists use silence in archaeology to argue against the Bible.

An absence of evidence is not an evidence of absence.

Now let’s look briefly at what archaeology and historians say instead.

Historians acknowledge the existence of Nebuchadnezzar, Evil-merodak (Amel-marduk), Belshazzar and Cyrus.

Based on various clay tablets and other inscriptions, historians also insert Neriglissar (Nergal-sharezer), Labashi-marduk and Nabonidus between Evil-merodak (Amel-marduk) and Belshazzar.

Most historians completely deny the existence of Darius the Mede, claiming instead that it was Cyrus who defeated Babylon, adding it to his existing kingdom of Persia, Media and Lydia.

Can archaeology and historians help to fill in gaps in the Bible chronology so that we can have a chronology we can have confidence in?

Please note that I’m not suggesting that we should listen to historians to correct “errors” in the Bible, because experience shows overwhelmingly that where popularly accepted history conflicts with the Bible, the conflict is eventually reconciled once extra evidence forces historians to accept the Bible, not the other way around!

I have continued exploring the available evidence and the ideas of historians to see if I can find any hints that would make their interpretation of archaeology integrate better with the Bible.

While writing Volume 6 of Terror on Every Side! I came up with a timeline which I could more or less accept, although it wasn’t entirely satisfactory, and I planned to follow this timeline in my second book about Daniel.

Now, the whole question of timing has been reopened by an article I found on www.academia.edu. The article has some strange ideas in it, but seems to fit better with the Bible and some radical ideas I had been toying with myself.

If you wish to open an account on Academia.edu, you can download the article “A Radical Review of the Chaldean and Achaemenid Periods” by Steve Phillips.

What if the three kings said to reign directly after Nebuchadnezzar were actually caretakers who looked after the kingdom during his madness?

The total time of their rule was between six and seven years, which seems coincidentally close to seven years, allowing for some changeover delays, accession years and so on.

So let’s consider how this suggestion might fit in with what the Bible tells us and what historians believe they know. Unfortunately, most historians discard the Bible’s information in this area, arguing (without any proof) that the book of Daniel was written hundreds of years later.

I consider the Bible more historically accurate and reliable than the other records historians hold on to so tightly. My reasoning is twofold: firstly, I believe the Bible is the word of a God who tells the truth; and secondly, history gives many examples where experts have denied what the Bible says, only for later experts to be forced to admit that what the Bible said was correct.[1]

Jeremiah 52:31 tells us that Evil-merodak/Amel-marduk began to reign in the 37th year of Jeconiah/Jehoiachin’s captivity.

When was that? Let’s put some dates together.

If the three kings said to follow Nebuchadnezzar were actually caretaker rulers, filling in for Nebuchadnezzar while he was mad, then Nebuchadnezzar went mad in about 560BC in the 44th/45th year of his reign.

The three kings who followed Nebuchadnezzar are believed to be:

So far, so good, but if Nebuchadnezzar regained his sanity at this time and resumed the kingship, how does that fit in with what historians believe happened?

Historians suggest that Belshazzar orchestrated a coup which deposed and killed Labashi-marduk and installed Belshazzar’s father, Nabonidus, as king.

Nabonidus, most historians suggest, was not connected in any way with Nebuchadnezzar or the royal family, although some suggest that he may have been married to another of Nebuchadnezzar’s daughters.

(Timeline last updated 9 February 2024.)

Now we come to the second radical idea, put in the form of a question: What if Nabonidus was another name for a recovered Nebuchadnezzar? Apparently Nabonidus means “Nabu be praised”, or more simply “God be praised” or “reverer of God” – in the same way that Baal simply means “lord” and is, as such, occasionally used for Yahweh (e.g., 2 Samuel 5:20)

Perhaps this is a humbled Nebuchadnezzar who has recognised the God of Israel as deserving of praise and renamed himself accordingly. If so, he chose not to use God’s name, Yahweh, which weakens the case as far as I am concerned but does not destroy it.

Nevertheless, Nabonidus continued to rule until Babylon was conquered, which historians believe occurred in 539BC when Belshazzar had his famous feast, saw the writing on the wall and died that night.

If Nabonidus was a renamed Nebuchadnezzar, it is also worth considering the queen or queen mother’s comment in Daniel 5:11:

“There is a man in your kingdom in whom is the spirit of the holy gods. In the days of your father, light and understanding and wisdom like the wisdom of the gods were found in him, and King Nebuchadnezzar, your father – your father the king – made him chief of the magicians, enchanters, Chaldeans, and astrologers,”

“In the days of your father” would normally suggest that the father was dead, but in this case could conceivably refer to his time of active, independent rule. Nabonidus is believed to have lived in Arabia for most of his reign, with Belshazzar ruling as regent – legally the second in command, but king in practical terms. On the other hand, “King Nebuchadnezzar, your father – your father the king” would make much more sense if Belshazzar really was Nebuchadnezzar’s son.

In summary, I have decided to adopt a chronology which makes the three kings believed by most historians to follow Nebuchadnezzar (Evil-merodak/Amel-marduk, Nergal-sharezer/Neriglissar and Labashi-marduk) into caretakers for a mad king rather than later kings ruling in their own right.

We will get to another radical readjustment later…

Notes

| ↑1 | Two examples will demonstrate this.

Firstly, in the past, historians and some Biblical scholars stated that the Law of Moses could not have been committed to writing in the time of Moses because writing was very rare at that time – mostly limited to inscriptions on stone (see “Prolegomena to the History of Israel” by Julius Wellhausen, section 5, paragraph 1, and also section X.I.2 where he states that Moses’ laws were not written down at that time), and that he could not have compiled the information in Genesis from earlier written records because writing simply did not exist then (“Old Testament Theology”, Volume 1 by Hermann Schultz, page 25 (1892 or 1895 edition)). A second example is where Luke, the writer of the Acts of the Apostles, refers to some senior officials in Thessalonica as “Politarchs” in Acts 17:6, 8 and other officials from the province of Asia as “Asiarchs” in Acts 19:31. The use of these terms was once dismissed as evidence of Luke’s ignorance or carelessness because archaeologists had found no evidence of these terms. Newer archaeological evidence, however, supports Luke’s accuracy and attention to detail. Unfortunately, the fight to have the Bible’s records accepted as accurate history is an ongoing battle. No sooner does one proof turn up to confirm the Bible narrative than the sceptics abandon that particular argument and come up with some other detail that they can question because it has not yet been proved unequivocally correct. Frankly, one has to question their motives in this. An honest appraisal of the many available examples should cause historians to view the Bible as their primary source of reliable history for the areas and times to which it refers. |

|---|